Does Graphene Have a High Melting Point?

Graphene is frequently described as one of the most heat-resistant materials ever discovered. This has led to a common question: does graphene actually have a high melting point?

This article explains how graphene behaves at extreme temperatures, why defining its melting point is scientifically complex, and how its thermal stability compares to other materials.

Why Graphene’s Melting Point Is Not Straightforward

Unlike bulk materials such as metals or ceramics, graphene exists as an atom-thin structure. Because it is only one atomic layer thick, graphene does not melt in the traditional sense observed in three-dimensional solids.

Instead of transitioning from solid to liquid, graphene tends to lose structural integrity through bond breakdown or sublimation under extreme thermal conditions.

Thermal Stability of Graphene

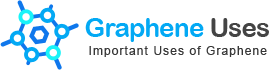

Experimental and theoretical studies suggest that graphene remains structurally stable at temperatures exceeding 4,000 kelvin under controlled conditions. This places graphene among the most thermally stable materials known.

Carbon–carbon bonds in graphene are exceptionally strong, allowing the lattice to withstand temperatures far beyond those tolerated by metals such as steel, aluminum, or copper.

Does Graphene Actually Melt?

In practice, graphene does not exhibit a clean melting transition. At sufficiently high temperatures, the atomic lattice begins to disintegrate rather than forming a liquid phase.

This behavior is similar to other carbon allotropes, where extreme heat leads to structural collapse or sublimation instead of conventional melting.

Comparison With Other High-Temperature Materials

When compared to materials commonly used in high-temperature environments, graphene demonstrates exceptional thermal resilience:

- Steel: Melts around 1,370°C

- Tungsten: Melts around 3,422°C

- Graphene: Structural stability beyond 4,000 K under ideal conditions

While tungsten remains one of the highest melting metals, graphene surpasses most materials in thermal endurance at the atomic level.

Practical Temperature Limits in Real-World Use

Although graphene’s theoretical thermal limits are extreme, real-world applications rarely approach these temperatures. In composites, coatings, or electronics, graphene’s performance is constrained by surrounding materials.

Polymers, substrates, and bonding layers typically degrade long before graphene itself is affected.

Why High Thermal Stability Matters

Graphene’s resistance to heat makes it valuable in applications involving high current flow, friction, or thermal cycling. It helps distribute heat efficiently, reducing hotspots and improving reliability.

This is why graphene is used in thermal interface materials, electronics, coatings, and energy systems rather than as a standalone structural material.

Limitations and Misconceptions

A common misconception is that graphene can replace all high-temperature materials. In reality, graphene’s atomic thinness means it must be integrated into composites or coatings to be useful.

Its heat resistance does not eliminate the need for conventional materials designed to withstand bulk thermal loads.

Future Research Directions

Ongoing research continues to explore graphene’s behavior under extreme conditions, including high pressure and combined thermal stress. These studies help refine models of two-dimensional materials and their limits.

Understanding graphene’s thermal breakdown mechanisms is essential for future aerospace, electronics, and energy applications.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does graphene have a melting point?

Not in the traditional sense. Graphene does not melt like bulk materials and instead breaks down at extremely high temperatures.

How hot can graphene withstand?

Graphene can remain stable at temperatures above 4,000 kelvin under controlled conditions.

Is graphene more heat resistant than metals?

Yes. At the atomic level, graphene can withstand higher temperatures than most metals.

Why doesn’t graphene melt like steel?

Because it is only one atom thick, graphene does not form a liquid phase before its structure collapses.

Is graphene used in high-temperature products?

Graphene is used to improve heat management in products, but it is typically embedded within other materials rather than used alone.